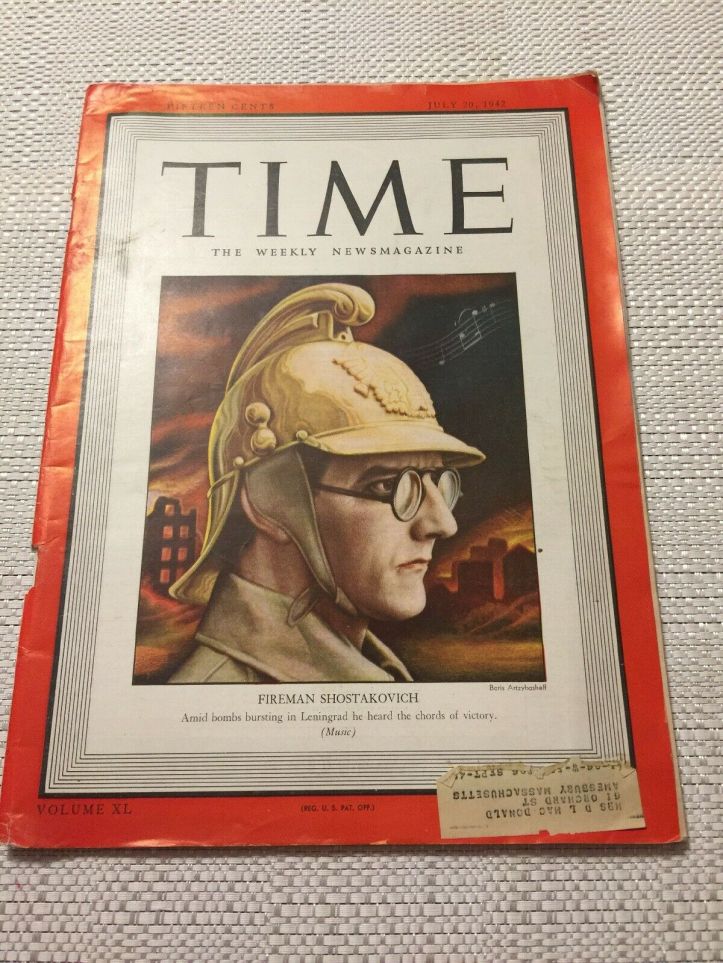

I recently got my hands on a copy of Time Magazine dating from 1942. I purchased it because of its iconic cover of Dmitri Shostakovich in his (slightly preposterous) fireman’s helmet, from the early days of the Siege of Leningrad. There is an article inside about the perilous journey of the score of the 7th Symphony to the United States, the conductors who vied to premiere it, a somewhat high-level review of the music itself, and background on the composer.

That’s not what this post is about precisely. Being someone with a sharp interest in the historical period between 1918 and 1945, the magazine interested me far beyond its cover subject. But we’ll start there, because it illustrates my point well:

When did we stop assuming Americans were intelligent and engaged with the world around them?

Time is about as mainstream as it gets. Apparently, in 1942, not only were Americans interested in Soviet composers of classical music, they would have known and recognized several prominent conductors: Toscanini. Koussevitsky. Stokowski. They might have tuned into NBC Radio to listen to the premiere of the 7th Symphony. Nobody was telling them it might challenge them because it wasn’t Beethoven, so they shouldn’t even try.

Go to 100 average Americans today, and ask them to name one–just one–conductor. Or contemporary composer, one active today. Ask them where they would go to hear the newest classical music compositions played. I’m betting that 95% of them would give you a blank stare.

Perhaps I am being too harsh. It could be rightly posited that the place most Americans hear orchestral music these days is in film scores. And major orchestras know that–witness the success of films accompanied by live orchestras playing the scores–whether it be the Star Wars movies, Harry Potter movies, Home Alone, or classic Hollywood repertoire. I will give you that. But apart from John Williams, I doubt whether most could name the composer of any of these scores. They certainly would be hard pressed to name the orchestras that played them for the movies–if only because orchestras rarely play for soundtracks any more. And that has changed in my lifetime. The original Star Wars soundtrack was performed by the London Symphony. The most recent Star Wars movie? A nameless studio orchestra.

But let’s look deeper into the magazine. Besides a fascinating review of Oscar Wells’ latest movie, The Magnificent Ambersons, and the debate surrounding it, the issue is packed full of intensely focused coverage of the war in both Europe and the Pacific, as reported by multiple sources. It also has a fascinating article Canadian politics (specifically regarding conscription) under William Lyon Mackenzie King, among other articles about politics. While Canadian politics certainly are covered to some extent in the US press today, particularly in publications aimed at a more educated audience, I was surprised to see that kind of article in what I would consider a mainline publication aimed at ordinary Americans.

And it’s not just that. In all of the articles, the vocabulary seems to be targeted at readers with a high level of reading comprehension and understanding. Remember, this is in an era when most Americans did not attend college. Yet I feel as if I am reading literature. Perhaps it’s just the perspective of 75+ years passed, the perspective of a time when magazines like these weeklies were devoured as the latest news by a public for whom they were one of the only windows they had to the world around them.

But I am left with the impression that publications like Time wrote at this level and about these topics because it was an aspirational publication. Smart people were interested in Canadian politics and Shostakovich symphonies–and these were things that average people, as a result, aspired to be interested in as well. And magazines like Time gave them that opportunity and assumed that they would get it. The articles do not condescend. They simply assume intelligence and engagement with the world.

It wasn’t that long ago, really, that Americans still liked smart people. The people who put us on the moon, the people who wrote fascinating books and plays and music that challenged us to think, to perhaps be a little uncomfortable because we did not have all of the answers right away. “Go, find out why,” the thinking seemed to be. “There is no shame in not knowing–only in lacking the curiosity to seek out answers.”

Too often now, it seems that what is popular is what is comfortable, that which wraps the reader in a warm blanket that soothes the creative rather than sparking it.

And this is sad. Because there are Americans–people all around the world–who are smarter than they’ve ever been–not because they were born geniuses, but because through hard work and dedication–some as individuals, some as part of teams–they have mined that curiosity for the gold of discovery, of artistry, of inspiration. And I love to listen to these people–because they make me smarter and make me think, and challenge me to never, ever stop learning.

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ Ignorance is not the death of democracy. The refusal to learn and to think certainly is. Actually it is the death of any viable society.

LikeLike